Kubla Khan

Or, a vision in a dream. A Fragment.

1.

In Xanadu* did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree

Where Alph*, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea. 5

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round;

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills, 10

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

2.

But oh! that deep romantic* chasm* which slanted

Down the green hill athwart* a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted 15

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst 20

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion 25

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war! 30

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device, 35

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

3.

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian* maid

And on her dulcimer she played, 40

Singing of Mount Abora.*

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ’twould win me,

That with music loud and long, 45

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair! 50

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.*

NOTES:

*”Xanadu may refer to:

a metaphor for opulence or an idyllic place, based upon Coleridge's description of Shangdu in his poem Kubla Khan

Shangdu, the ancient summer capital of Kublai Khan's empire in China”

*”Alph River, a river in Antarctica; Alph Lake, a lake in Antarctica; Alph, a fictional river in the poem Kubla Khan by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.”

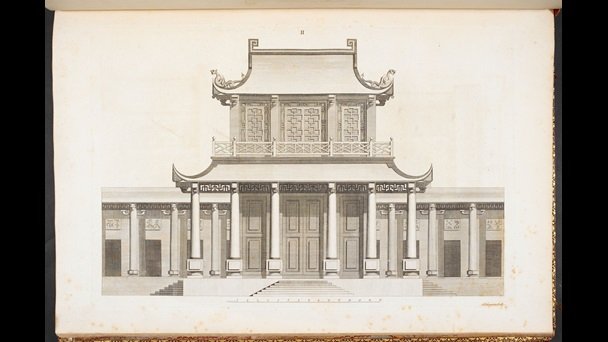

Image:

William Chambers’s Designs of Chinese Buildings, Furniture, Dresses, Machines and Utensils (1757) was drawn from the author’s years spent in China; it described Chinese design in a way that was more authentic than most previous writing on the subject.

*The Ethiopian Empire, also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia, was an empire that historically spanned the geographical area of present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. Wikipedia

*1 : across especially in an oblique direction. 2 : in opposition to the right or expected course and quite athwart goes all decorum— William Definition of romantic

*Entry 1 of 2) 1 :consisting of or resembling a romance. 2 : having no basis in fact : imaginary. 3 : impractical in conception or plan : visionary.

*a yawning fissure or deep cleft in the earth's surface; gorge. · a breach or wide fissure in a wall or other structure. · a marked interruption of continuity; gap ...

*”Some critics have suggested that Mount Abora is Coleridge's name for Mount Amara, the mountain described by John Milton in Paradise Lost at the source of the Nile in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) -- an African paradise of nature here set next to Kubla Khan's created paradise at Xanadu.”

*The only gaps in the text are at the 3 numbers; the other gaps between lines are my inability to format texts properly.

COMMENTS;

In the first stanza the narrator is looking at an exotic, “Xanadu,” a distant foreign place where the ruler, Kubla Khan, a despot of sorts, one assumes given his famous ancestor, has ordered the construction of a “stately pleasure dome.” The interesting element is the perspective of distance and perhaps holiness present in the first stanza. Xanadu is not next door; Alph is a fictional “sacred” river (like the Ganges, perhaps), and it disappears underground in images again suggesting distance ( as well as darkness) from the narrator (and reader): the caverns are “measureless to man.” That area then suggests an unattainable distance and reality.

Immediately, however, the narrator returns to the idea of distance—“So twice five miles of fertile ground—enclosed with human structures that contain wonderful, enchanting, perhaps, gardens. The language continues the idea of beautiful, exotic places, desirable but not really specific. The ground is “fertile,” the many gardens are “bright with sinuous rills,” and the trees, no flowers though, appeal to the senses since they are “incense-bearing.” Also within this ten mile enclosure there are “forests ancient as the hills” which enfold “sunny spots of greenery.” Now there are more trees, “ancient” suggesting distance again but the only specific element there is a color—green. Thus, in stanza one, we have a series of images that suggest sensuality and pleasure but that are also distant from us. It’s a reality that is essentially created by the vague and suggestive language that seems to present us with a yearning for it, only to have it yanked from us in stanza two.

The change in stanza #2 is suggested immediately in the narrator’s “But oh!” The “chasm” and its violent nature seem to be the primary subject or image of stanza #2. Presumably he is referring to the place where the river disappears into a deep fissure in the ground, though calling the chasm “romantic” suggests an emotionally pleasant place, which the rest of the language almost immediately cancels or denies. From a suggested waterfall (“slanted”) in an intense landscape tumbling down a steep incline opposite to a possible grove of cedars. Now the narrator experiences nature, no longer a garden, but a “savage place!” To convey the nature of the savage place and the enchantment he compares it to a “haunting by a woman bewailing her demon-lover” beneath a “waning moon.” Here again we experience a real sense of distance and otherness as he focuses on a possible demonic presence in nature through the behavior of the river and chasm, as well as the image of the woman yearning for her “demon lover”.

At this point nature as chasm becomes incredibly violent, eventually throwing up a fountain as well as huge “dancing rocks.” The energy released in the imagery is powerful on the one hand—“ceaseless turmoil seething,” the fountain forced up, the entire earth seeming to “pant” from the activity, then the image of hail rebounding, and “chaffy grain” being separated by more violent activity, “the thresher’s flail; and finally the river itself seems to re-emerge only to “meander” this time with “a mazy motion / Through wood and dale the sacred river ran.” It seems to be meandering for five miles and then be running only finally to sink to where the poem began:

“Then reached the caverns measureless to man, /

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean,” instead of to a sunless sea.

This odd “tumult” is picked up in the next line by Kubla Khan where the nature or substance of it is shifted from the violent behavior of nature to the violent nature of humanity: now the distance involves the past, “ancestral voices,” that are “prophesying “ war! The tumult of nature and the tumult of war seem to be mixed together in the sounds heard by Khan (and the narrator) only to become surprisingly quiet or perhaps unreal as what we see is only the shadow of the pleasure dome reflected in the waves of the sacred river. And given the value of the sacred we now have before us a “miracle of rare device / A sunny pleasure dome with caves of ice.” Two senses come into play, seeing and hearing, and yet, much as I delight in the language of the poem, the images, the sounds and sights, I find that I do not believe any of it, for the poem exists for its tremendous effects in the mind of the narrator rather than in any truly imagined reality. Thus the images may contradict one another and be inconsistent—sunny / sunless; five miles / ten miles / measureless; dancing boulders / hail / grain and chaff; “momently” (twice) / yet time to meander five miles in a “mazy” like lazy motion. What the poet / narrator really seems to be doing is playing with the language as it comes to him in rhyme and rhythm because, like the image of the stately pleasure dome, the exercise is extremely pleasurable. Thus whether the images cohere or not does not really matter, and the poet / narrator can turn to a new series of somewhat magical, mystical images in the third stanza.

Stanza #3 involves another somewhat startling shift of new elements, as well as of the inclusion of old ones, the original images of stanza #1. The third person narrator of stanzas 1 and 2 now fully enters the poem in the first person, but again introduces an exotic image once more distant from him (and us) yet one he truly yearns for. The alliteration catches us immediately: “A damsel with a dulcimer / In a vision once I saw:” The rhythm of the first line is the regular iambic 8 (-/ -/ -/ -/), but the second line contains only 7 syllables, thus forcing us to emphasize “once” (/ -/- / -/), and thus removing that experience from the immediate presence. Past tense: “It was an Abyssinian maid / And on her dulcimer she played / Singing of Mount Abora.” In a rhythmic way the first 5 lines of this stanza [37-41] remind me (us?) of the first 5 lines of the poem [1-5]: (8 / 8 / 8/ 8 / 6 ; vs 8 / 7 / 8 / 8 / 7; and a / b / a / a / b [assuming “Khan” to rhyme with ran and man]; vs a / b / c / c / d ). While the first 5 lines of the poem are enclosed in a sense in the rhyme, “decree / sea,” the first five lines of the third stanza [37-41] are not, “dulcimer / Abora.” Remembrance seems to be the key to the section of the verse that immediately follows [42-47], for if he could “revive,” bring back to life within his mind, remember, the “symphony and song” she sang and played, one that possibly reminded him of Paradise, as the first lines of the poem seem to have as well with its garden imagery, he would then have won (as if it were a contest) the power from the pleasure and delight in the music to create the original images of the pleasure dome and the caves of ice, substantially, but in the air because what is bringing that about is music, thus hearing as well as bringing about seeing. Here again I experience in the narrator a sense of yearning for an exquisite pleasure, the pleasure of Eden or of Heaven from which he appears to be eternally cut off or separated.

The surge of creative power that the music “would” give him [48-54] would be such that all who heard and then saw would be should be terrified, he believes, and would immediately express their fear of that creative power in a dire warning with voice—“Beware! Beware!”—and with violent action—bind him—“Weave a circle round him thrice.” Particularly revealing is that the poet is telling the see-ers and the hear-ers what they “should” do to keep the tremendous power in check. He attributes his powerful, magician-like (a necromancer, perhaps, as suggested from Purchas’s text ?) appearance to the crowd: they should see this: “His flashing eyes, his floating hair.” Not only should (again) they cry out a warning, not only should they bind him, but they should also “close your eyes with holy dread.” And another reason for those actions, besides the power of his creativity, is indicated: “For he on honey-dew hath fed / And drunk the milk of Paradise.” While the poet / narrator has a yearning for that which has been lost—the language, the music, and the power—he also reveals, I think, that there is something demonic about his desires, the desire for a particular personal pleasure in fact. Perhaps, pleasure not grounded in the love for God is perverted; none of the pleasures in the text suggest that desire. Instead, they are all images and pleasures that enhance the human ego, especially the ego and power of the poet with language. Thus the poem is powerful in its use of language but always suggests a person cut off from his desire, thus alienated from a reality that he desires. Even though he may have drunk the milk of Paradise, he is none the less cut off from the Paradise that he ought truly to desire. One might say finally that this poem is about the power of the poet and that it suggests the possible right use of that power, one that the poet / narrator does not himself truly see.

As a suggestion one might turn to “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” to see how the poet fulfills the proper task of the poet, the revelation of the truly transcendent. As in Eliot’s “Hippopotamus” this narrator does not see what his powerful, beautiful language truly reveals, his failure to see that which is truly desirable, the transcendent in the human and in the natural. That he is alienated from both is evident in the poem; what is not evident is his understanding of the reason or his failure to understand the reason. I think the poem is complete and takes us as far as it possibly could, especially ending with the word “Paradise.”

[Somehow I accidentally screwed up the formatting again, accidentally hitting something I shouldn’t have hit! Frustrating! Just as I was doing so well. Perhaps second son can help me out when he returns. Sigh!]

New Criterion vol. 40 #8 April 2022. Essay on AI by Carmine Starnino: On artificial intelligence and creativity.

“Stephen Marche, writing an article for The New Yorker, assigned gpt-3 [the AI computer program] maybe the trippiest poem in the English canon: Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s fifty-four-line “Kubla Khan”—an opium dream interrupted in the middle of its composition in 1797 and never completed. gpt-3’s mission? Finish the fragment. What the program fantasized was so sophisticated (“The tumult ceased, the clouds were torn,/The moon resumed her solemn course”) that readers unfamiliar with the original poem might have had a hard time discerning where Coleridge ended and the computer began.”