Essay #1 George Weigel [First Things;

“Easter Changes Everything”. 4/4/12

Christmas occupies such a large part of the Christian imagination that the absolute supremacy of Easter as the greatest of Christian feasts may get obscured at times. Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, an Italian biblical scholar, suggests that we might begin to appreciate how Easter changed everything—and gave the birth of Jesus at Christmas its significance—by reflecting on the story of Jesus purifying the Jerusalem Temple, at the beginning of John’s Gospel.

In this prophetic and symbolic act, Ravasi writes, Jesus draws a sharp contrast between a religion of superficiality and self-absorption and a pure faith, centered on his person. God can no longer be present in a Temple that has ceased to be a place of encounter, the “meeting tent” of the ancient Hebrews; that Temple, however magnificently constructed, had become a place of superstition and self-interest. In cleansing the Temple, Jesus is declaring that God is now present to his people in a new and perfect way and in a new “meeting tent”: the incarnate Son, “the Word . . . made flesh” who dwells among us, “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). He, Jesus, is the new Temple, and to recognize that and live in this new mode of the divine Presence one must “remember,” as St. John writes at the end of the Temple-cleansing story (John 2:22).

And remember what? Remember Easter. Remember the Resurrection. Through the prism of that extraordinary event that changed both history and nature, everything comes into clearer focus. Only a mature, paschal faith—an Easter faith—can perceive who Jesus is, understand what Jesus taught, and grasp what Jesus has accomplished by his obedience to the Father. Only in the power of this paschal “memory,” Cardinal Ravasi concludes, can we recognize that Jesus is the Christ, the Holy One of God.

Easter faith—the faith which proclaims that “he . . . rose again on the third day”—is not one article of Christian conviction among others. As St. Paul teaches in 1 Corinthians 15, Easter faith is that conviction on which the entire edifice of Christianity is built. Without Easter, nothing makes sense and Jesus is a false prophet, even a maniac. With Easter, all that has been obscure about his life, his teaching, his works and his fate becomes radiantly clear: this Risen One is the “first-born among many brethren” (Romans 8:29); he is the new Temple (Revelation 21:22); and by embracing him we enter the dwelling place of God among us (Revelation 21:3).

In the Gospel readings of the Easter Octave, the Church annually remembers the utterly unprecedented nature of the paschal event, and how it exploded expectations of what God’s decisive action in history would be. No one gets it, at first; for what has happened bursts the previous limits of human understanding. The women at the empty tomb don’t understand, and neither do Peter and John. The disciples on the road to Emmaus do not understand until they encounter the Risen One in the Eucharist, the great gift of paschal life, offered by the new Temple, the divine Presence, himself. At one encounter with the Risen Lord, the Eleven think they’re seeing a ghost; later, up along the Sea of Galilee, it takes awhile for Peter and John to recognize that “It is the Lord!” (John 21:7). These serial episodes of incomprehension, carefully recorded by the early Church, testify to the shattering character of Easter, which changed everything: the first disciples’ understanding of history, of life-beyond-death, of worship and its relationship to time (thus Sunday, the day of Easter, becomes the Sabbath of the New Covenant).

Easter also changed the first disciples’ understanding of themselves and their responsibilities. They were the privileged ones who must keep alive the memory of Easter: in their preaching, in their baptizing and breaking of bread, and ultimately in the new Scriptures they wrote. They were the ones who must take the Gospel of the Risen One to “all nations,” in the sure knowledge that he would be with them always (Matthew 28:19-20).

They were to “be transformed” (Romans 12:2). So are we.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

ESSAY 2

“He Is Risen” R. R. Reno

5/2/11 [First Things]

I spent Easter in Omaha. The Great Vigil liturgy at St. Cecilia’s Cathedral was transcendent, with the music of Vittoria, Palestrina, and Byrd providing exquisite accents to contemporary plainsong. But it’s the beginning that always hits me in the gut. My heart beat faster with each urgent declamation of the Exsultet, the ancient hymn sung after the procession of the paschal candle that culminates: “This is the night when Jesus Christ broke the chains of death and rose triumphant from the grave.”

The Resurrection. It’s the central truth around which the Christian faith turns. And when I went home after the service while savoring a glass of bourbon filled to a decidedly post-Lenten level, I chuckled over a Nebraska memory. Some years ago I spent a spring evening at the University of Nebraska engaging a fallen-away Fundamentalist in a debate: Is it reasonable to believe that Jesus was raised of the dead?

There’s no doubt that the writers of the New Testament thought of themselves as giving reasons. Aside from the disputed ending of Mark, the gospels give eyewitness testimony to the risen Lord. So to a great degree the question is whether this evidence counts for anything. That evening in Lincoln, Nebraska, the skeptical former Fundamentalist argued that the scriptural accounts are untrustworthy.

One argument he made drew attention to the diversity of resurrection accounts that portray Jesus differently. Reliable testimony, he suggested, requires agreement.

But is that right? Imagine that you are on a jury and all the witnesses provide identical accounts. Wouldn’t you become suspicious? It’s not normal for people to observe and remember events in the same way, especially not unexpected and traumatic events. Moreover, as we know, the gospels were written decades after Jesus’ death and resurrection, and in the case of the Gospel of Luke by someone who admits that he relies on the testimony of others. Given the passage of time, it becomes even more unlikely that the accounts would match up nicely.

An analogy might help. Imagine that there was a lynching in a small town in Georgia in 1920. Now imagine that some forty or fifty years later town leaders and their now grown children feel compelled to write about the event, one fraught with intense emotions and painful memories. Imagine further that their accounts agree in detail, emotional tone, and sequence of events. Remarkable! Indeed so remarkable that a reasonable person would begin to suspect that communal mythology has come to replace actual memories, creating a false and perhaps reassuring harmony. Thus, it seems to me that the overall harmony rather than detailed agreement between the gospels makes it more rather than less reasonable to believe their testimony.

Another argument the ex-Fundamentalist made that night concerned the obvious partisanship of the New Testament. Yes, that’s quite true, but does zeal and conviction undercut testimony?

Here another analogy helps. Imagine that you want to know about the Game of the Century (which for the uninitiated refers to the epic struggle between Nebraska and Oklahoma in 1971 that featured a brilliant punt return by Johnny Rogers and, of course, the ultimate triumph of the Cornhuskers). You visit an older couple. The husband was and remains a rabid fan who has attended every home game since 1963. His wife has little interest in football, though she went to the Game of the Century because, as a newlywed she had yet to figure out how to absent herself.

Now I ask you: Whose account is more likely to be accurate? Yes, the husband may embellish, and his memory may be gilt with nostalgia. But in all likelihood he paid close attention, and his passion for football keeps his memories alive. His wife? True enough, she’s dispassionate and in a sense more “objective.” But that counts against her testimony, for she’s far less likely to have brought her mental powers fully to bear upon the game—and far less likely to sustain in her memory what she experienced.

The same goes for the writers of the gospels. Their passionate belief in the resurrection of Jesus does not necessarily count against the value of their testimony. On the contrary, in many ways we rightly trust a committed, living memory much more than an uncommitted and dispassionate memory.

Thus I think it’s reasonable to say that Christians have scriptural reasons for believing in the resurrection. A skeptic might judge these reasons insufficient (and on this point I’m inclined agree). Few believe simply because of the direct testimony of the New Testament. But that doesn’t mean that the gospels provide empty or inconsequential reasons for an Easter faith.

There are more powerful, indirect reasons in favor of belief in the resurrection, ones that stem from the fact that, as I pointed out above, the Easter affirmation plays a central role in the Christian faith. As St. Paul put it: If Christ is not risen, your faith is vain (1 Cor. 15:17). In view of this centrality, our broader reasons for believing in the truth of Christianity in general support our belief in the resurrection in particular.

Some are like the travelers on the road to Emmaus. They are struck by the way in which the death and resurrection of Jesus throw a striking light upon puzzling passages in the Old Testament. Others feel the transformative power of Christian teaching, or encounter the remarkable and enduring substance of the Church and her sacramental life, or find the witness of the saints inspiring. In each case and countless others, the evidence suggests that there’s something to Christianity, and thus, insofar as one understands the logic of Christian affirmations, to the resurrection as well.

Of course, many think that the something is best understood as a sociological need for institutions, or a psychological need for belonging, or a credulous instinct that has evolutionary value, and so forth. None of the evidence in favor of the resurrection compels us in the way that a scientific experiment might. But, again, that’s not the point. What’s reasonable need not be so certain or self-evident that it generates a strong consensus.

In fact, a strong consensus is rare, not common. Consider politics. Should we say that our greatest challenge is income inequality or lack of economic opportunity? Climate change or stagnant growth? Indeed, people cannot even agree about whether or not an unborn child is a person. Should we be surprised, then, that the evidence in favor of Christianity is interpreted in many different ways, sometimes as reasons in favor, and at other times as reasons against?

No, of course not. Given the profoundly personal and consequential character of Christian faith—eternal life!—it’s absurd to imagine that its central affirmation, the resurrection, can be supported a cool, objective, widely shared consensus. Or more precisely: it’s a cynical debater’s trick to conjure such a possibility, and then call Christians irrational for failing to secure it.

As I sipped my bourbon in the late hours of that most blessed of all nights, chosen by God to see Christ rising from the dead, I found my warm recollections of debate drifting toward a cooler state of self-observation. “Yes,” I thought to myself, “Jesus may not have risen from the dead, and my faith may be empty.” Unlike square circles, that’s a real possibility. Fair enough, it conceded to the debater in my mind. “But,” I replied, “it’s very foolish indeed to think that what might be false cannot be true.”

R.R. Reno is Editor of First Things. He is the general editor of the Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible and author of the volume on Genesis. His previous “On the Square” articles can be found here.

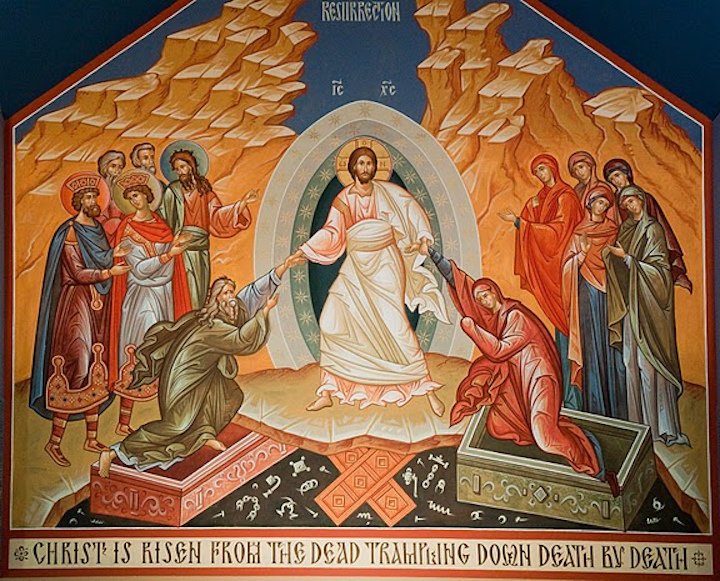

Image: A modern iconic representation of the 11th-century fresco known as the Anastasis, located in the former Chora Church in Istanbul, which was converted into a mosque in the 16th century, then into a museum in 1945, and, in 2020, became the Kariye Mosque.