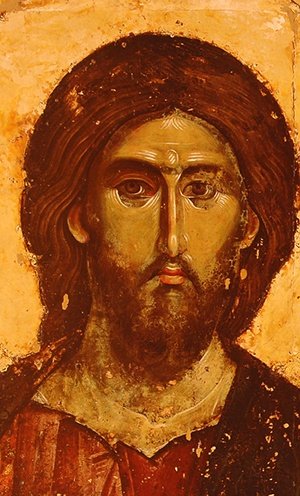

Seeking the Face of God

Anthony Esolen

I’ve often thought that one of the tremendous mysteries of the Jewish faith was that God forbade the people to make any graven images. Everywhere else in the world, man makes his gods in the image and likeness of himself, whether of his body or of the ghoulish projections of his soul. Sometimes we get a hideous Moloch, eager to devour little children. Sometimes we get a handsome Apollo, god of song and sunlight—also of mice and the plague.

But not in Israel. And that makes it all the more powerful when we read that God knew the great prophet and lawgiver Moses face to face (Dt 34:10), and when the singers of Israel long to behold the face of God. They did not yet know the incarnate Lord, nor could they conceive of that incomparable blessing upon mankind. The very angels must tremble before that blessing, as Christ sits at the throne of God, son of both God and man, anointed universal king.

What did they mean? Rather, what did God mean, when he commanded them to seek his face?

The song of the beloved

I ask that question whenever I read Psalm 27, the brilliant song of triumph that David sang—David, whose name means beloved. The first three verses express his firm trust that God will protect him from his enemies, even if they come against him in an army. The Hebrew verb suggests that they turn on him, they come down. Imagine them as rushing down from a height upon the otherwise helpless David below. “Yet I will be confident,” he cries, because God is “the stronghold of my life.”

And then suddenly the poem turns. I cannot read the words without a flush of surprise and gratitude, and wistful longing:

One thing I have asked of the Lord,

that will I seek after;

that I may dwell in the house of the Lord

all the days of my life,

to behold the beauty of the Lord,

and to inquire in his temple.

The word we translate as “behold” is almost never found in the Bible except in poetry—the poetry of prophecy, of contemplation, of ecstatic vision. The psalmist cannot merely be talking about going to the temple in Jerusalem to look upon the finery. Surely the Holy Spirit is raising him to an intimation of what he cannot explain. And who could explain it? The Lord is not an abstraction. His beauty is real, achingly real. Why, we find a form of the same word when the bridegroom in the Song of Songs praises his bride: How fair and pleasant you are, O loved one, delectable maiden! (7:7).

Then English fails us in the final phrase. What does it mean to “inquire” in the temple? Inquire about what? Are we to engage in an investigation? Yes and no. The verb, baqar, suggests discernment, reflection. The Hebrew would have heard an echo of one of the most significant words at the beginning of creation itself: boqer, morning, daybreak. The idea is that, in prayer, in contemplation, you break into the truth. Not by your own power, though. We may say that God allows the truth to break into you, to dawn on you. Imagine then the beauty of God’s glory suddenly breaking upon you in your natural darkness.

Booths on a mountaintop

From the temple, the psalmist turns back to the world of trouble, but now, so to speak, the house of God accompanies him:

For he will hide me in his shelter in the day of trouble;

he will conceal me under the cover of his tent,

he will set me high upon a rock.

In English, nowadays especially, we are apt to think of shelter as an abstraction, as if all that the psalmist means is that God will protect him. He does mean that, but the Hebrew word, sukkah, is far more evocative. Think of the lean-tos that the people of Israel dwelt in, when they fled from Egypt into the desert, and made their slow way to the Promised Land. The Lord then commanded them always to celebrate the happy harvest-time feast of booths, Succoth, for seven days in the seventh month, beginning five days after the great and solemn Day of Atonement, and ending with a kind of anticipation of Easter, the eighth day, a day of holy convocation.

What the Hebrews did was to gather the boughs of beautiful trees, and branches of palm and willow, weaving them together for a booth, that is, a shady makeshift house, to sit beneath, and to eat and drink there, and rejoice in God’s plenty. The contrast between the work of human hands—a temple in stone, a screen of leafy branches soon to wither away—and the work of God is striking. Better to dwell beneath the lean-to of God than to depend upon princes and armies!

That makes me think again of what Saint Peter said when the Lord was transfigured on the top of the mountain, appearing there with Moses and Elijah. Master, it is well that we are here; let us make three booths, one for you and one for Moses and one for Elijah (Mk 9:5). He was, the evangelist says, not in his right senses when he said it, because he and James and John were all in great fear. But it was exactly the thing to say. Somehow, Peter sensed that the Lord was instituting a new Feast of Booths, so to speak, just as he would build a new temple, one not made by human hands.

The enemies return

The poet alternates verses singing praise to God, and hoping to enter the mystery of God’s house, with verses that call for help against his enemies. When we read the psalms, we may wonder who the poet’s enemies were and what they were doing to him, but we never wonder that he has enemies. I suppose that enmity is the world’s common state of affairs. Liars expose you to hatred and scorn. Swindlers play upon your innocence or your kindness. The envious want to tear you down, and so they twist your very virtues into vices.

Treachery is worst, when people whom you have helped turn against you, or when those from whom you expect kindness abandon you to your enemies. For my father and mother have forsaken me, says the psalmist, but the Lord will take me up. It is not just to hide him away and keep him safe:

And now my head shall be lifted up

above my enemies round about me;

and I will offer in his tent sacrifices

with shouts of joy;

I will sing and make melody to the Lord.

It is hard to translate the Hebrew ruwa’—think of an ear-splitting shout, or the blast of a trumpet on the battlefield. And after the shout, the songs and the melodies; not so that the Lord will raise him up, but because he has done so, and has raised him up for song and praise. Man never stands so tall as when he sings praise to God, and gives the Giver of all good things what is the closest he can come to a pure gift. You can put a house to use, you can swing a sword to protect your people, but praise is akin to gratitude, and only the truly free heart can give it.

The Holy of Holies

And now comes what for me is one of the most staggering verses in all of Scripture:

Hear, O Lord, when I cry aloud, be gracious

to me and answer me!

You have said, “Seek my face.” My heart says to you,

“Your face, Lord, do I seek.” Hide not your face from me.

No pagan Greek sought the face of Zeus. Why seek what your sculptors sculpt? No Egyptian sought the dog-face of Anubis. But the face of our God must be sought: and how else, but by love? Here it is not a comely form that shows itself to us first, and we delight to look upon it. “Where there is love,” says the mystic Richard of Saint Victor, “there is an eye.” We love, and then we see. Our Lord himself says to us, Seek, and you shall find, and no one seeks the face of the beloved, unless love has come first.

The great evangelist of love, Saint John, must have been thinking about this verse, and about the face of the Lord he loved, when he said, Beloved—and in his mind, as he thought in his native tongue, he surely heard the name of the Psalmist—we are God’s children now; it does not yet appear what we shall be, but we know that when he appears we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is (1 Jn 3:2).

What do we want from God? No pagan Roman wanted Saturn, cold and morose. No pagan Viking wanted Thor, that muscular half-wit. We want to say, with the psalmist, You are my portion, O Lord (Ps 119:57). We want to be set free from sin and from the prison of fallen man, to see God, whom to see in truth is to love, and whom to love is to love eternally.

Anthony Esolen is professor and writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts in New Hampshire, translator and editor of Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House).