[Another essay I wanted to keep track of and reread. Published in the U of Notre Dame’s Church Life Journal April 5, 2022. A Journal of the McGrath Institute for Church Life] LES

Stephen M. Barr

“Is Science of Any Help in Thinking About Heaven?”

Catholics and other Christians believe that those who are saved shall have eternal life. But where will that life be lived and what shall it be like? Will it be within the confines of this physical universe or altogether beyond it? Will it be anything like the present state of things, physically speaking, or utterly different? Is science of any help in thinking about these things, or is it completely irrelevant?

The Destiny of the Physical Universe

Perhaps the best place to start is by asking what will happen, ultimately, to the physical universe we currently inhabit. Many scriptural texts say that it will pass away. In Psalm 102 we read, "Long ago you laid the foundation of the earth and the heavens are the work of your hands. They will perish, but you endure; they will all wear out like a garment. You change them like clothing, and they pass away."

Christ himself declared, “Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (Matt 24:35). St. Paul told the Corinthians, “The present form of this world is passing away” (1 Cor 7:31). The First Letter of St. John says, “And the world and its desire are passing away” (2:17). The Second Letter of St. Peter foretells that “the present heavens and earth have been reserved for fire . . . the heavens will pass away with a loud noise, and the elements will be dissolved with fire” (2 Pt 7, 10).

What does present science tell us? According to the standard Big Bang theory, the universe has two possible fates. One is that it will continue to expand forever, growing ever colder, darker and emptier. Eventually, all the stars will burn out, having consumed their nuclear fuel, and all other forms of usable energy will be exhausted. This has traditionally been called the “heat death” of the universe, because all heat would be gone and all life with it.

The other possibility is that the universe will eventually stop expanding and start contracting. As it contracts and compresses, it will become increasingly hot and dense, ultimately reaching such an inconceivable temperature that even space and time will shrivel away. This is the so-called “Big Crunch” (like the Big Bang in reverse), at which point the universe and physical time itself would presumably abruptly cease. Obviously, in this case, too, all life in the universe would have an end.

Which fate is more likely? Before 1998, they seemed equally so, but in that year it was discovered that the expansion of the universe has been speeding up for the last few billion years, which points away from a Big Crunch and towards a heat death; but there is a lot we still do not know and the question remains open. In any event, long before any cosmic disaster occurs, the Sun will explode to become a “Red Giant” in about five billion years, incinerating any life that might still exist on earth. A 1920 poem by Robert Frost began, “Some say the world will end in fire, some say in ice.” We now know that the earth will end in fire. As for the universe itself, we do not know which way it will end, but that it will end as a place where any life can exist appears certain.

It would seem, then, that modern cosmology and biblical revelation are in basic agreement. However, theologically, things are not quite so clear-cut. Scripture and tradition are somewhat more ambiguous about the fate of the cosmos than at first appears. For, although Scripture speaks in many places of heaven and earth passing away, it also speaks of the coming of a “new heaven” and a “new earth.” “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away” (Rev 21:1). This echoes Isaiah 65:17: “For I am about to create new heavens and a new earth; the former things shall not be remembered or come to mind.”

The “new heavens” and “new earth” could be understood in two ways: either as a total replacement of the present heavens and earth, or as their transformation and renovation. Many scriptural passages are suggestive of the former, since they speak of the present world simply “passing away.” And, as we saw, Psalm 102 uses the image of a garment being changed. On the other hand, the passage from First Corinthians quoted above says more specifically that the “present form of this world” is passing away, which seems to imply that although the world will have a new form, it will still be “this world.” Theological tradition supports this understanding. Section 1047 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, for example, states that “the visible universe . . . is itself destined to be transformed.” Moreover, Romans 8:20-21 speaks of the universe ultimately being “set free”: “The creation was subjected to futility . . . in the hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God.”

Many theologians take this pregnant but mysterious passage to mean that the universe will “redeemed” by being transformed in such a way that it will no longer be a place of death and decay. That last notion would be problematic, however, if one were to assume that the transformed universe would be a “physical universe” strongly resembling the present one, i.e., a realm in which there are matter, space, and time that are governed by the same or similar “laws of physics.” For, in that case, it would seem unavoidable that the law of entropy and therefore death and decay would continue to hold sway. As we shall see, however, there are strong theological and scriptural reasons for doubting that the new heavens and new earth will be “physical” in that sense.

A point about Romans 8:20-21 that seems significant is that it links the liberation of the cosmos to the “freedom of the glory of the children of God.” This suggests that its redemption will be achieved in and through the redemption of human beings and their ultimate glorification in heaven. One way to think of that is as follows. If God’s intention for the physical universe was that it should bring forth the children of God, and his intention for the children of God was that they should attain eternal life with him in glory, then through the redemption of those children the universe would attain its goal and fulfillment and overcome the “futility” to which it otherwise would have been condemned.

St. Thomas Aquinas understood the redemption of the physical universe as occurring through human redemption, since human beings carry within themselves all the levels of being found in the cosmos: the physical, the organic, the sentient, and the rational. Joseph Ratzinger, in his book Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, summarized St. Thomas’s view as follows:

It is in that movement [of the human person toward God] that the material world, indeed, comes into its own, by stretching forth towards God in man. In man’s turning to God “all the tributaries of finite being in all its variety of level and value, return to their Source.”

Following that train of thought, one could even imagine that what continues of this world into the next is redeemed humanity.

The Resurrection of the Body

The question of what the next world will be like leads, of course, to the question of what kind of bodies the redeemed will have after the “resurrection of the dead,” a question that St. Paul himself confronted in his first letter to the Corinthians. “But someone will ask,” he wrote, “How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?” (1 Cor 15:35). On the one hand, the very word “resurrection” (“rising again”) implies that the “risen” body will be the same body as that which died, something that the early Church Fathers and subsequent tradition have unanimously affirmed.

It is, indeed, de fide Catholic teaching. On the other hand, the precise sense in which the risen body will be “the same body” has never been defined. While historically the great majority of Catholic theologians have understood this to imply some material continuity, a minority have held that what will make it the same body is that it will be united with the same spiritual soul. There is, however, no definitive magisterial teaching on this question.

In any case, any hypothesis that posits a continuity that is physical—in the sense of “that which physics studies”—between this universe and the “new heaven and new earth” and between human bodies in this world and resurrected bodies in the next raises some thorny questions. The chief one, already mentioned, has to do with the fact that things in this physical universe are inherently “corruptible” or “perishable,” i.e., subject to inevitable aging, decay, and dissolution, whereas in the next world there will be no decay or death.

The corruptibility of things in this universe is a consequence of the Second Law of Thermodynamics (the law of entropy). And it would apply not only to this universe with its particular physical laws, but probably to any physical universe that resembled ours in basic respects. And that is because the Second Law of Thermodynamics is a rather general consequence of the laws of probability and depends very little upon the details of the laws of physics. The idea that a physical realm continuous with and strongly resembling this universe could be immune to corruptibility, death, and decay, is problematic.

One person who grasped the basic issue with great clarity was St. Paul himself, who discussed it at length in First Corinthians 15:35-55. There he states flatly that “flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God, nor does the perishable inherit the imperishable.” And for this reason, he says, an abrupt “change” must occur at the resurrection: “We will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. For this perishable body must put on imperishability.”

How this will happen, he confesses, is “a great mystery.” He emphasizes that the resurrected body, being imperishable, must differ greatly from the earthly body, differing as much from it as a wheat plant differs from the “bare seed” from which it sprang. A “spiritual body,” he says, must replace the “animal body” (or, as it is usually translated in English, the “physical body” or “natural body”). Joseph Ratzinger in his Introduction to Christianity summarized St. Paul’s teaching on the resurrection of the body in this way:

Thus, from the point of view of modern thought, the Pauline sketch is far less naïve than later theological erudition with its subtle ways of construing how there can be eternal physical bodies. To recapitulate, Paul teaches, not the resurrection of physical bodies, but the resurrection of persons, and this not in the return of the “fleshly body,” that is, the biological structure, an idea he expressly describes as impossible (“the perishable cannot become imperishable”), but in the different form of the life of the resurrection, as shown in the risen Lord.”

The “Bodily” and the “Physical”

In thinking about these issues, it might be helpful to consider human bodies from two distinct, though obviously related, perspectives: the physical-biological on the one hand, and the personal on the other. From a physics perspective, the bodies of plants and animals have a single purpose, namely maintaining the organism (and its kind) in existence against the universal tendency of all that exists in this world to perish. As some have pithily put it, biological organisms are “survival machines.” In order to understand better what this entails, some basic physics explanations are needed.

What the Second Law of Thermodynamics says is that “entropy” (a mathematical measure of physical disorder) always increases with time, and order decreases. At first sight, this principle would seem to rule out the growth and development of plants and animals, for in organic growth and development matter in less ordered forms (e.g. water, air, soil, and nutrients) becomes incorporated into the highly ordered structures of an organism’s body. However, what the Second Law of Thermodynamics says, more precisely, is that disorder, as measured by entropy, always increases (or at least never decreases) on the whole. This qualification is important, for the Second Law allows entropy to decrease (and thus order increase) in one place or in one physical system as long as entropy increases elsewhere by even more. It is the total entropy that cannot decrease.

A good illustration of this is that you can decrease the entropy of a glass of water by putting it in the freezer of your refrigerator, causing the disorderly motions of the H2O molecules in the liquid to give way to the orderly arrangement of the molecules in the crystals of ice that form. But that decrease in entropy inside the freezer is more than compensated by an increase of entropy outside the freezer. In particular, energy flows into your freezer in the more ordered and usable form of electrical power, and comes out again in the less ordered form of heat (as you can tell by feeling the warm air coming out of the back of the refrigerator). As this example illustrates, for a system to go against the universal tendency to disorder generally requires an input of usable energy from outside the system. If you unplug the refrigerator, the food inside will eventually spoil and the ice melt.

The key point is that the growth, development, and life of organisms is able to “buck the trend” of the physical world toward disorder because they are able to make use of external sources of energy. (The ultimate source of energy for all life on earth is the Sun, or in some cases geothermal energy.) The same is true of the evolution of living things from less organized forms.

The struggle of living things in this universe for survival is thus largely a matter of obtaining usable energy. That is why animals have to eat and breathe. Every part of the body of a biological organism has a function that in some way serves the purpose of counteracting the universal entropic tendency toward corruption and decay. That is why the human body has an alimentary system for the ingestion, digestion, and absorption of nutrients; a respiratory system; a multiplicity of sensory systems that enable it to find nourishment and avoid dangers; a host of defense mechanisms, including an immune system and bodily integument, that allow it to avoid becoming nutriment for other organisms, both macroscopic and microscopic; a reproductive system to carry the species forward; and so on with every organ and cell of the body.

Of course, human beings are much more than survival machines. We are persons, endowed by God with reason, free will, and the capacity for love and self-transcendence. And this leads us to consider the other, higher purpose of our bodies: interpersonal communion. Human beings interact with each other not only physically but personally, and we do both only through our corporeality. Only through external signs and gestures and deeds can we know each other’s minds and hearts and receive and express love. Our communion with God is also only through our corporeality, through Word and sacrament.

This is not to say that the two purposes of the human body, the physical-biological and the interpersonal, are not related to each other; they obviously are. Our capacity and need for interpersonal communion are rooted in our sociality, which has its roots in that of our animal forebears. And the sociality of animals clearly plays many roles in survival, otherwise it would not have evolved. But what began at the animal level as cooperation, care, and even affection is raised to a higher level in human beings. A family meal is not just a matter of physical sustenance, but of deep spiritual bonds.

If our bodies have a twofold purpose in this life, what about in the next life? Well certainly their role as mediators of interpersonal communion, both with God and other human beings, will remain. It is precisely through our incorporation into the Body of Christ that we will have such communion. Indeed, it could be said that the completed Body of Christ, including both its Head and all of its human members, is heaven itself, which is achieved (as the Letter to the Ephesians says) when “all of us come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ” (4:13). Joseph Ratzinger in Eschatology: Death and Eternal Life, put it this way:

The perfecting of the Lord’s body in the pleroma of the “whole Christ” brings heaven to its true cosmic completion. Let us say it once more before we end: the individual’s salvation is whole and entire only when the salvation of the cosmos and all the elect has come to full fruition. For the redeemed are not simply adjacent to each other in heaven. Rather, in their being together as the one Christ, they are heaven.

But what of the other purpose of the bodies we have in this life, the physical purpose as “survival machines”? Clearly that purpose is gone in the next life, as there will be no “corruptibility” and death that must be staved off by physical activity. The medieval Scholastic theologians agreed that what they called the “vegetative” functions of the human body would not be needed and would therefore not operate in heaven, though it was their belief that the organs associated with those operations would remain, in order that the risen bodies be perfect and complete.

There are several hints, or more than hints, in Scripture that various physical functions of the body are not present or not needed in heaven. The Book of Revelation, referring to the New Jerusalem, which is an image of heaven, says, “And the city has no need of Sun or Moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb” (21:23). This suggests that the kind of light that Sun and Moon shed—physical light, made up of electromagnetic waves—will no longer be present because no longer needed. Those in heaven will not need to find their way by such light, as they did in this physical universe; and that would seem to imply that they will have no physical need for such things as retinas, optic nerves, and so forth. Their only Light shall be God himself, “For in Thy light shall we see light” (Ps 36:9).

Nor will physical food and the organs and processes of digestion be needed to provide physical energy. St. Paul tells the Corinthians that “’Food is meant for the stomach and the stomach for food,’ and God will destroy both one and the other.” He then immediately goes on to talk about the body’s role in communion: “The body is meant . . . for the Lord, and the Lord for the body. And God raised the Lord and will also raise us by his power. Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ?” (1 Cor 6:13-15).

Those in heaven will need no physical food, for their food will be Christ. Not earthly bread, but the Word that “proceeds from the mouth of God” (Matt 4:4; Sir 24:3). In his Confessions, St. Augustine recounts a mystical experience he and his mother St. Monica shared at Ostia shortly before her death, where they both ascended in spirit and had a glimpse of “that region of never-failing plenty, where Thou feedest Israel for ever with the food of truth.” The food of truth is, of course, Christ himself, the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

Nor will the reproductive functions of the body be needed, for, as Jesus told the Sadducees, who were arguing against the resurrection of the dead based on their overly physicalist conception of it, “For in the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven” (Matt 22:30). Of course, the fact that certain bodily parts and functions that are needed in this life to deal with the challenges imposed by physical “corruptibility” will no longer be needed for that purpose in the next life does not necessarily imply that they will not be present or serve other purposes. Their roles, in that case, would no longer be so much physical and biological, but would subserve the purpose of interpersonal communion.

Moreover, none of this is to say that resurrected bodies, because less “physical” in a certain sense will be somehow wispy, etherealized, and less real than our bodies in this life. If anything, our corporeality in the next life will be more real, more substantial, and our present forms will seem ethereal in comparison to it—to use St. Paul’s words, as a mere “tent” compared to a solid “building”:

For we know that if the earthly tent we live in is destroyed, we have a building from God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. For in this tent we groan, longing to be clothed with our heavenly dwelling—if indeed, when we have taken it off we will not be found naked. For while we are still in this tent, we groan under our burden, because we wish not to be unclothed but to be further clothed, so that what is mortal may be swallowed up by life . . . So we are always confident; even though we know that while we are at home in the body we are away from the Lord (2 Cor 5:1-6).

The Glory of Heaven

A common argument—which is very traditional, and thus very weighty—is that we have a fairly good idea what resurrected bodies will be like, as we have descriptions of how Christ’s resurrected body appeared to the disciples. That is true; and that body certainly was very physical—the resurrected Christ ate fish with the disciples; they saw him with their eyes and heard him with their ears; and he invited doubting Thomas to put his hand into his pierced side. But, of course, Christ had to appear to the disciples in a physical way if they were to be witnesses to his resurrection, as they were still living in this physical universe and could only perceive him with physical senses. This raises the question of whether what the disciples were capable of witnessing in this way was the full reality of resurrected bodies as they shall be in the world to come. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, in section 659, suggests otherwise:

But during the forty days when he [the resurrected Christ] eats and drinks familiarly with his disciples and teaches them about the kingdom, his glory remains veiled under the appearance of ordinary humanity. Jesus's final apparition ends with the irreversible entry of his humanity into divine glory, symbolized by the cloud and by heaven, where he is seated from that time forward at God's right hand.

What the redeemed shall have in the world to come is bodies that have “entered into divine glory.” As St. Paul told the Philippians, “He will transform the body of our humiliation that it may be conformed to the body of his glory, by the power that also enables him to make all things subject to himself” (Phil 3:21). What that will be like remains “veiled” from our sight.

There is a curious contrast between two post-Resurrection appearances of Christ, which may have some significance with respect to the two purposes of human bodily existence. Christ tells St. Thomas to touch him—indeed to put his finger into the nail marks and his hand into his side; but he tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him: “Touch me not, for I am not yet ascended to my Father” (Jn 20:17). Perhaps the difference was in what they were seeking. Thomas was seeking mere physical proof of a physical body. He was the prototypical scientific skeptic! But Mary was seeking something far more profound: communion with her Lord. But the level of communion she was seeking had to await Christ’s ascension.

We are left then with “a great mystery,” as St. Paul told us. One of the striking features of the New Testament is that we are not tantalized with descriptions of heaven in terms of earthly delights, as in the numerous, sensuous (not to say sensual) descriptions of paradise given to Muslim believers in the Quran. The New Testament is remarkably reticent on the details of the next life. One might have expected otherwise, if believers were to be given added incentive, beyond the promise that they will be with God and participate in the divine life.

But, as St. Augustine said in the Confessions, even the “very highest delights of the earthly senses” are “not worthy of comparison” with “the sweetness of that life” or “even of mention.” We are told in Scripture that what awaits the redeemed in the world to come is far beyond our present capacity to fully understand or imagine: “What we will be has not yet been revealed” (1 Jn 3:2) and “What no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the human heart conceived what God has prepared for those who love him.” (1 Cor 2:9).

Author

Stephen M. Barr

Stephen M. Barr is professor of physics and director of the Bartol Research Institute, University of Delaware. He is the president of the Society of Catholic Scientists and author of bestselling books on science and religion such as Modern Physics and Ancient Faith (Notre Dame) and The Believing Scientist (Eerdmans).

EDITORIAL NOTE: This article is part of a collaboration with the Society of Catholic Scientists (click here to read about becoming a member). A version of this article with extensive foonotes is available here.

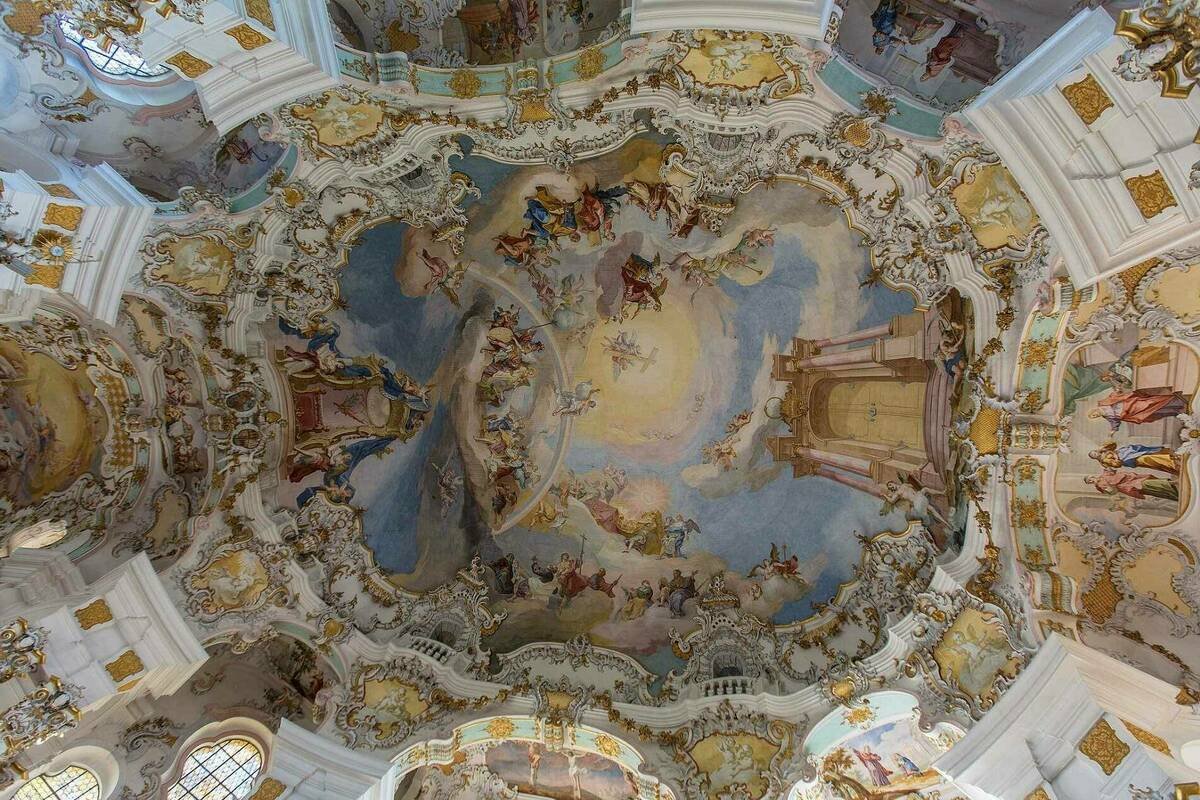

Image: Featured Image: Photo taken by Harro52 Fresco of the flattened dome ceiling in Wieskirche by Johann Baptist Zimmermann; Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.