For the detective Jack Colt, as I suspect for many men, women are beautiful, desirable and essentially mysterious. In the third volume of William Baer’s New Jersey Noir trilogy, near the end, Jack visits one of the beautiful women in the hospital. We see immediately that she is very “pretty,” as are all of the women he names from all three novels a bit later. Savannah, the injured woman on the hospital bed, wants to know about the nature of their relationship: “What are we, Colt?” You can read his response in what follows:

She looked up at me. It was hard to ignore how pretty she was, even with her head bashed in. “What are we, Colt?”….

“We’ll figure it out,” I said.

Which I said without the slightest conviction that I could ever “figure” it out.

Or figure out Zoe. Or Roxs. Or Rikki O’Brien, the girl from Cape May two months ago. All of whom deserved a whole lot better than me.

Which I don’t say with some kind of self-effacing sense of self-demeaning modesty. I’ve got nothing but confidence about myself. I know myself. Thank you, Socrates.

Except in regards to the irresistible sex.

“What time is it?”

I looked at my watch. “Just past midnight.”

“You can go home, Colt. I think I’m stoned anyway.”

I laughed.

“Are you sleepy?”

“Like Snow White after the apple.”

I laughed again.

“Kiss me before you go.”

I bent over and did as commanded.

Why are women so delicious?

Am I allowed to say that?

I felt better.

Which was all her doing….

Jack Colt in New Jersey Noir: Barnegat Light, book 3 in the delightful trilogy by William Baer (Emphasis mine).

___________________________________________________________________________

As I said above, for Colt throughout the three novels, women are incredibly beautiful, desirable, and essentially mysterious. Of course the author has Jack give a nod to the semantic confusion in our culture by asking the reader, “Am I allowed to say that?” Needless to say, I suppose, I think so. In fact when we don’t make a distinction between male and female qualities, masculine and feminine, we lose the opportunity to understand something significant about the meaning of being human generally, and especially about ourselves.

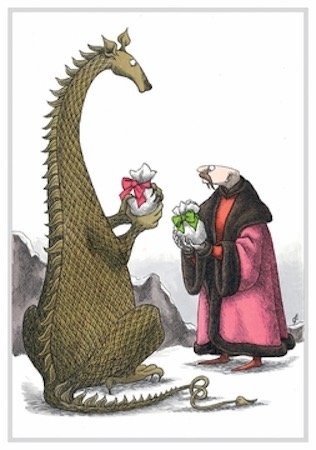

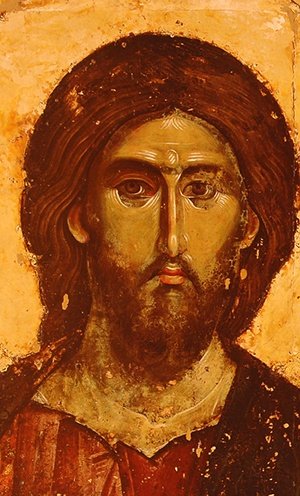

In other words, to limit my comments to the experience I, as a man, know something about: what does feminine Beauty mean? In our culture the lowest common denominator in male/female relationships is sex, and unfortunately that’s where the meaning is likely to stay in our rabbit culture. Of course a beautiful woman is desirable, but that isn’t the end, sex isn’t the end. What does her beauty really mean? Is she just an idol, an end in herself, or is she an icon or image, a means for beholding something essentially transcendent, the real meaning of Beauty? If students today were given the opportunity to read classical texts with someone who understood them, an answer might manifest itself, as it does in Dante’s La Vita Nuova and in his Divine Comedia or in Shakespeare’s plays, The Tempest, for example, or in Milton’s exquisite portrait of Eve and Adam in his Paradise Lost or his delightful masque, Comus.

Advertising especially turns feminine beauty into an idol in order to sell products. “Her” beauty leads men to a desire that ends up in bed as if having sex can somehow let you possess that beauty, but what you get instead is: “an expense of spirit in a waste of shame,” more than likely; that is, according to the Shakespearean sonnet, “the definition of “lust in action.” That is also the lowest common denominator and the loss of an opportunity to understand.

So what does human desire mean first according to the classical, orthodox Christian theologians? See the following definition. Second, what does Dante have to reveal about feminine beauty and its meaning? That’s below too, after the theological explanation.

___________________________________________________________________________

“Desire is given so that we can understand the purpose for which we are living.

“To pray is to exercise our desire. St. Augustine tells us that ‘the desire of your heart is itself your prayer. If you wish to pray without ceasing, do not cease to desire. The constancy of your desire will itself be the ceaseless voice of your prayer.’ In a mystical dialogue, God says to St. Catherine of Siena, ‘Do you know how I show myself within the soul who loves me in truth? I show my strength in many ways according to her desire.’

“Why is desire so crucial? We realize from experience that our desires are taking us somewhere. Desire opens us up to an exciting plan bigger than ourselves, and it entices us to go after it. C.S. Lewis speaks of desire as ‘the secret signature of each soul, the incommunicable and unappeasable want. The thing itself has always summoned you out of yourself.’

“God also says to St. Catherine, ‘I who am infinite God want you to serve me with what is infinite, and you have nothing infinite except your soul’s love and desire.’

“Be aware that desire itself is God’s gift to us, and desire is given so that we can understand the purpose for which we are living. St. Thomas Aquinas assures us that ‘there is no desire which is not directed towards a good. A natural desire cannot possibly be vain and senseless.’

“Our desires are given to us precisely to lead us to the One who gave them to us. Desire is given so that we can participate personally in the happiness of the One who created us. And ‘we can only really possess what we desire’ (G. Bernanos).

“The Catholic poet Paul Claudel offers this encouragement: ‘Christ tells us, I have come to bring you the desire and the direction, that secret understanding, throughout your travels, of your destination. To the burden that weighs you down, I have added longing.’ Let’s give in to our longing and let desire do the heavy lifting in our prayer as we ask with St. Cyprian: ‘May God see our desire, for he will give the rewards of his love more abundantly to those who have longed for him more fervently.’” Fa. Peter John Cameron. (Aleteia)

___________________________________________________________________________

Benedict XVI on St. Augustine: “In a beautiful passage, Saint Augustine defines prayer as the expression of desire and afiirms that God responds by moving our hearts toward him.”

___________________________________________________________________________

As with Jack Colt and his typically human desire for the beautiful women in his life, here are four brief examples of how the Biblical poems and prophets understand the fundamental human longing for God as the central human desire:

Isaiah 26:8-9

Indeed, while following the way of Your judgments, O Lord,

We have waited for You eagerly;

Your name, even Your memory, is the desire of our souls.

At night my soul longs for You,

Indeed, my spirit within me seeks You diligently;

For when the earth experiences Your judgments

The inhabitants of the world learn righteousness.

_____________________

2. Psalm 42:1-2

As the deer pants for the water brooks,

So my soul pants for You, O God.

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God;

When shall I come and appear before God?

____________________

3. Psalm 63:1-8

A Psalm of David, when he was in the wilderness of Judah:

O God, You are my God; I shall seek You earnestly;

My soul thirsts for You, my flesh yearns for You,

In a dry and weary land where there is no water.

Thus I have seen You in the sanctuary,

To see Your power and Your glory.

Because Your lovingkindness is better than life,

My lips will praise You.

_____________________

4. Psalm 73:25

Whom have I in heaven but You?

And besides You, I desire nothing on earth.

(Source: https://bible.knowing-jesus.com/topics/Desires)

___________________________________________________________________________

As in the case of Jack Colt, his delight in and desire for beautiful women are immediately clear throughout the three novels. And I should add that he doesn’t sleep around! He simply seems to appreciate their beauty and their desire ability. Jack Reacher, however, does sleep around and what a difference it makes when I think about the novels in comparison. Baer’s novels allow for the possibility of mystery and transcendence in their male/female relationships; Child’s novels do not. Reacher has a personal moral code, but Child’s novels are completely grounded in the material world. Colt appreciates, Reacher beds.

It ought to be clear from the above theological passages that the purpose or the final cause of desire in the human self, man and woman, theologically understood, is to lead us to God. Dante is the poet who defines for us the way in which “romantic” desire fits into this understanding of the desire for God.

First, however, you might think of the way Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, an earlier literary source, unfolds. Romeo and Juliet’s love and their desire for one another is unquenchable. But there is a third thing with them throughout the entire play until it manifests itself more explicitly in the end, and that is of course death! Romantic love of itself can lead only to death. Or to put the idea into its theological context it can also lead either to Heaven or to Hell. To understand how it can lead to Hell, consider the famous lovers in the Inferno: Paolo and Francesca, and how their love, their desire for one another, went wrong. For the opposite destination see the entirety of Dante’s poetry, especially starting with his Chapter 19 in La Vita Nuova.

___________________________________________________________________________

(The following “chapter 19” is from Dante’s La Vita Nuova as translated by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. [If I knew how to tighten the stanzas I would, but every time I attempt such things, everything falls apart. This time I do not blame my failure on the imp (of the perverse), but who knows for certain.]. Each stanza of this Canzone is 14 lines. The reason for including this poem at this point is that here Dante reveals how love, desire and image work, or ought to work in human romantic relationships. Dante’s desire and love for Beatrice, the real human woman, becomes the means by which he comes to understand Beauty, Grace, Goodness, and God and thus to desire God. Whew!

______________________

“XIX After which it happened, as I passed one day along a path which lay beside a stream of very clear water, that there came upon me a great desire to say somewhat in rhyme; but when I began thinking how I should say it, methought that to speak of her were unseemly, unless I spoke to other ladies in the second person; which is to say, not to any other ladies, but only to such as are so called because they are gentle, let alone for mere womanhood. Whereupon I declare that my tongue spake as though by its own impulse, and said, “Ladies that have intelligence in love.” These words I laid up in my mind with great gladness, conceiving to take them as my commencement. Wherefore, having returned to the city I spake of, and considered thereof during certain days, I began a poem with this beginning, constructed in the mode which will be seen below in its division. The poem begins here:

Ladies that have intelligence in love,

Of mine own lady I would speak with you;

Not that I hope to count her praises through,

But telling what I may, to ease my mind.

And I declare that when I speak thereof

Love sheds such perfect sweetness over me

That if my courage fail’d not, certainly

To him my listeners must be all resign’d.

Wherefore I will not speak in such large kind

That mine own speech should foil me, which were base;

But only will discourse of her high grace

In these poor words, the best that I can find,

With you alone, dear dames and damozels:

’Twere ill to speak thereof with any else.

An Angel, of his blessed knowledge, saith

To God: “Lord, in the world that Thou hast made,

A miracle in action is display’d

By reason of a soul whose splendors fare

Even hither: and since Heaven requireth

Nought saving her, for her it prayeth Thee,

Thy Saints crying aloud continually.”

Yet Pity still defends our earthly share

In that sweet soul; God answering thus the prayer:

“My well-beloved, suffer that in peace

Your hope remain, while so My pleasure is,

There where one dwells who dreads the loss of her;

And who in Hell unto the doom’d shall say,

‘I have look’d on that for which God’s chosen pray.’”

My lady is desired in the high Heaven:

Wherefore, it now behoveth me to tell,

Saying: Let any maid that would be well

Esteem’d keep with her: for as she goes by,

Into foul hearts a deathly chill is driven

By Love, that makes ill thought to perish there;

While any who endures to gaze on her

Must either be made noble, or else die.

When one deserving to be raised so high

Is found, ’tis then her power attains its proof,

Making his heart strong for his soul’s behoof

With the full strength of meek humility.

Also this virtue owns she, by God’s will:

Who speaks with her can never come to ill.

Love saith concerning her: “How chanceth it

That flesh, which is of dust, should be thus pure?”

Then, gazing always, he makes oath: “Forsure,

This is a creature of God till now unknown.”

She hath that paleness of the pearl that’s fit

In a fair woman, so much and not more;

She is as high as Nature’s skill can soar;

Beauty is tried by her comparison.

Whatever her sweet eyes are turn’d upon,

Spirits of love do issue thence in flame,

Which through their eyes who then may look on them

Pierce to the heart’s deep chamber every once.

And in her smile Love’s image you may see;

Whence none can gaze upon her steadfastly.

Dear Song, I know thou wilt hold gentle speech

With many ladies, when I send thee forth:

Wherefore, (being mindful that thou hadst thy birth

From Love, and art a modest, simple child,)

Whomso thou meetest, say thou this to each:

“Give me good speed! To her I wend along

In whose much strength my weakness is made strong.”

And if, i’ the end, thou wouldst not be beguiled

Of all thy labour, seek not the defiled

And common sort; but rather choose to be

Where man and woman dwell in courtesy.

So to the road thou shalt be reconciled,

And find the lady, and with the lady, Love.

Commend thou me to each, as doth behove.